Level Up Your Stretching With PAILs And RAILs

February 21, 2022 | Assessments

If you’ve ever been to our gym or taken one of our KINSTRETCH classes, you know we do exercises called PAILs and RAILs. But what are they?

PAILs and RAILs are acronyms we use to describe a method of stretching from Functional Range Conditioning (FRC). As you’ll see, it makes much more sense to abbreviate this method rather than calling it its full name.

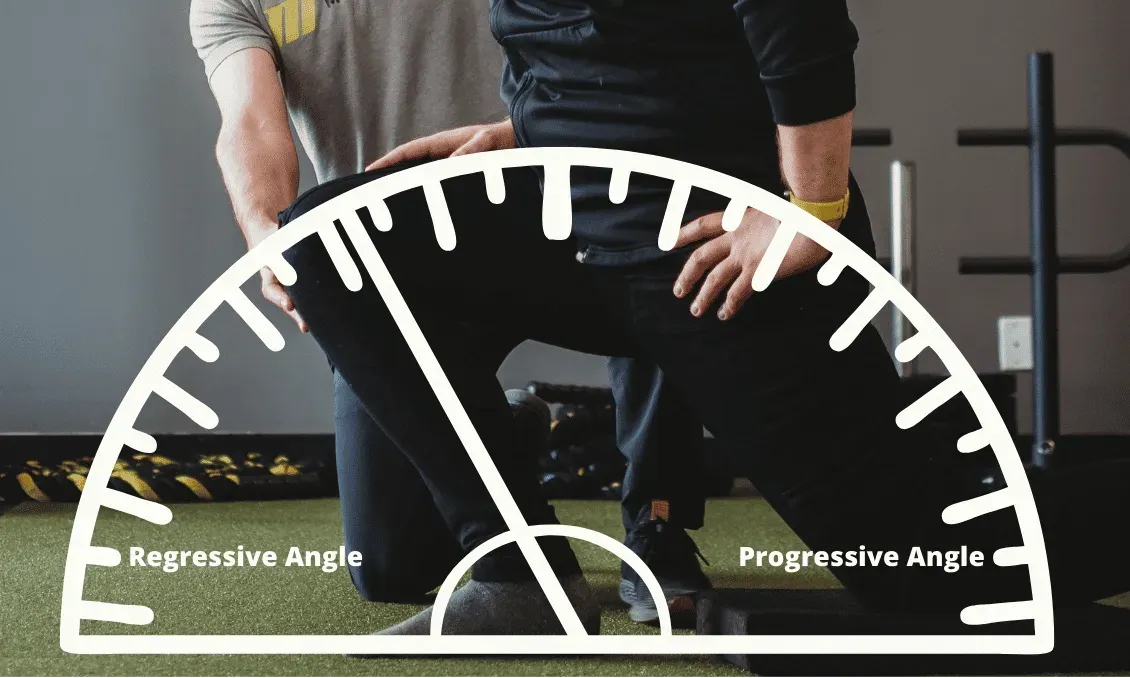

PAILs and RAILs are part of the Functional Range Systems developed by Dr. Andreo Spina. PAILs stands for Progressive Angle Isometric Loading, while RAILs stands for Regressive Angle Isometric Loading.

We use PAILs/RAILs to create permanent changes in a given joint, improving range of motion, tissue architecture, joint control, and more. Importantly, PAILs & RAILs are designed with safety in mind, making them a secure and effective method for joint improvement. In other words, PAILs & RAILs are the bee’s knees.

Progressive & Regressive Angle Explained

The progressive and regressive angle refers to the joint itself.

The progressive side of the joint is undergoing lengthening because the angle is increasing; this is the same side being stretched.

The regressive side of the joint shortens because the angle decreases; we also call this the closing side of the joint.

Let’s use ankle dorsiflexion as an example. The progressive side of the ankle is the calf because it is undergoing length; the regressive side is the shin because the angle is closing.

The Benefits Of Isometric Loading

An isometric contraction happens when a joint creates force, but there is no motion. Examples of isometric contractions include progressive angular isometric loading (PAILs) and regressive angular isometric loading (RAILs). Although the fitness industry doesn’t often use isometric contractions, they are an instrumental tool you should put in your arsenal. For instance, isometric contractions are:

- Safe. They allow us to create extremely high magnitudes of force with little risk because the load (resistance) does not exceed the capacity of the joint you’re working on. So, for instance, if you push up against a brick wall as hard as you can, there’s a small risk for injury; the joint is more likely to yield to the wall from contractual, neurological, or biological failure versus injury.

- Scalable. You can dictate how much effort and intensity you want to put into an isometric contraction.

- Controllable. You can choose what lines of tissue you want to focus on (i.e., different muscles or connective tissues in a given joint).

- Repeatable. Isometrics generally allow faster recovery times because the subsequent muscle damage tends to be less than the conventional full range of motion exercises (1).

The law Of Irradiation

Sherrington’s Law of Irradiation states, “A muscle working hard recruits the neighboring muscles, and if they are already part of the action, it amplifies their strength. The neural impulses emitted by the contracting muscle reach other muscles and ‘turn them on’ as an electric current starts a motor.” - This quote was taken directly from the Functional Range Conditioning course.

PAILs and RAILs impact the nervous system by training it to control and function in newly acquired ranges of motion, enhancing muscle recruitment and active control.

Simply put, if we’re attempting to work a muscle or tissue with the appropriate intent, effort, and intensity, it behooves us to create irradiation (systemic tension). For example, if we’re attempting to stretch the tissue that moves the ankle, it may be helpful to create full-body tension to innervate the work we’re doing at the calf/ankle.

This is why we recommend irradiation/tension when doing anything related to FRC; it allows us to put our energy into the right places.

The Protocol

The PAILs/RAILs protocol can be used in many ways, but a few key points are worth highlighting. PAILs/RAILs can be applied to various joints, including improving end-range hip flexion and hip internal rotation. Since you already have the visual, we’ll continue using the ankle as our example.

The first step is to find the stretch. Traditional approaches often involve holding passive stretches, but PAILs/RAILs offer a more effective technique by actively engaging and strengthening the end range of motion.

1) Find The Stretch

First, we want to isolate the tissue we’re targeting and put it under as much passive length as we can muster. This often requires patience and time, which is why the general recommendation is to sit in the stretch position for at least two minutes. Furthermore, stretching for longer durations will yield better tissue architecture changes you’re likely seeking anyway. (2)

You can sit in the stretch position for as long as needed (e.g., three to five minutes). While passive stretches are useful, combining them with PAILs/RAILs techniques can improve mobility.

To keep yourself focused and occupied, we recommend focusing on your breath. You can breathe in for a 4-count and exhale for a 4-count repeatedly.

2) Irradiate

Once we’ve sat in the stretch long enough, we irradiate and create body tension. You can isometrically engage muscles surrounding the joint or the entire body. The more things we lockdown, the better results we will get from the joint we’re working on.

Keep breathing. Don’t hold your breath; instead, take shallow breaths (think belly breathing, but not as deep).

3) Maximum Voluntary Contraction (MVC)

MVC is a scale we use to gauge direct effort and intensity; think of it as slowly turning a dial if you were turning up the volume in your car.

Once we’ve sat in the stretch for at least two minutes, we’ll slowly engage the progressive (stretching) tissue. To err on the safe side, we start at a low MVC (usually less than 10%) and work toward our maximum safest contraction.

For the ankle, we would slowly gas pedal the foot (without moving anything), trying to get the tissue on the back of the calf to fire up. Then, as we build tension, we increase the force going into the ankle and calf, going from 10% to 100% as slowly as needed.

Editor’s Note: You don’t always have to work to 100% MVC. Sometimes, 50% is all you need to get the desired result.

4) PAILs Contraction

The PAILs contraction is our maximum safest contraction; we’re trying our very hardest to get the calf muscle to lengthen under as much isometric load as we can manage.

We hold this contraction for at least five seconds, but this will change depending on the intent.

5) RAILs Contraction

The RAILs contraction is our maximum safe contraction but on the closing angle side of the joint. So now we’re trying to get the shin muscles to pull us into the deepest stretch position we can manage.

We hold this contraction for at least five seconds, but this will change depending on the intent.

Editor’s Note: Like everything else, the PAILs/RAILs contractions at the end can be shorter or longer depending on what is needed. Five seconds is a bare minimum recommendation.

6) Find The Stretch Again

Let all the tension go. Relax. Try to find the stretch again. Sit here as long as you’d like and try to relax into it gently.

TL;DR.

Okay, this might seem like a lot to take in, but it’s a simple concept.

- We find lines of tension in a tissue and put them under length. For ankle dorsiflexion, we’re looking to stretch the back of the calf for time.

- We slowly start to engage the lengthened tissue (calf muscles). We use a term called maximum voluntary contraction, or MVC. Think of this as a sliding scale from 0 to 100%; you can voluntarily contract a muscle gently or hard as hell, depending on how much effort you put in. Generally, we work from 0% to 100% MVC, as you’ll see next.

- We build to a max-effort contraction (i.e., you’ll try to engage the muscle we’re stretching fully) and hold it for some time. This is PAILs.

- We eventually shift and try to maximally engage the opposite muscles (e.g., if we’re stretching the calf, we will switch to trying to engage your shin muscles) for some time. This is RAILs

- Boom! Improvements in how the joint works.

Here’s a quick demo of me setting up for ankle dorsiflexion PAILs/RAILs to tie it all together.

I hope this sheds more light on the PAILs/RAILs process. However, no amount of written text is going to help you feel what it’s like to go through your first PAILs/RAILs. If you have joints that don’t work right, achy or painful body parts, or simply want to learn how to move with purpose, I highly suggest you schedule a call with us today.

We’ll bring new meaning to the word “stretching.”

References:

Written by:

Brian Murray, FRA, FRSC

Brian Murray, FRA, FRSC

Founder of Motive Training

Do you want us to show you how to do PAILs and RAILs effectively? Reach out to us using any of the contact forms on the Motive Training website, and we’ll take care of you.

We’ll teach you both how to move with purpose so you can lead a healthy, strong, and pain-free life, and we’re available online or in Grand Rapids, MI, and Austin, TX. You can find us in the Heartside district of Grand Rapids, MI, and the St. Elmo district in South Austin, TX.